5/5

To be entirely honest, I bought a ticket to this show1 on a whim. I was idly browsing the NT website after realising that the show I have been meaning to go to has sold out, and when I saw the word ‘scandal’ next to the figure ‘£20’, I thought ‘why not’.

I went into the Dorfman Theatre with rather moderate expectations, partly because a rather awful show I watched way back had somewhat tainted the venue for me by association, but more so because I was not expecting too much from a play tagged with both politics and identity. By experience, from political plays one could expect a few archetypal characters mixed into a rather flat base of chronological narrative, inoffensively spiced up with conflicts along familiar partisan faultlines, and topped off with a dash of dry wit —- much like a single G&T on a weekday evening. Works exploring cultural identities, meanwhile, are often a bit hit or miss —- if a writer (or director, or producer, etc) deliberately panders to a (real or imagined) ‘diverse’ audience, they run the risk of turning a good story into a sad assemblage of shallow archetypes and hollow cultural symbols in pursuit of ‘relatability’.

I left the Dorfman with my mind blown. The only thing I could say over the next half an hour or so was ‘wow’. I really cannot think of a better play out of the countless ones I have seen in London over the past few years, and it would not be an exaggeration to say that this play has single-handedly reset my expectations of plays dealing with politics and/or identity.

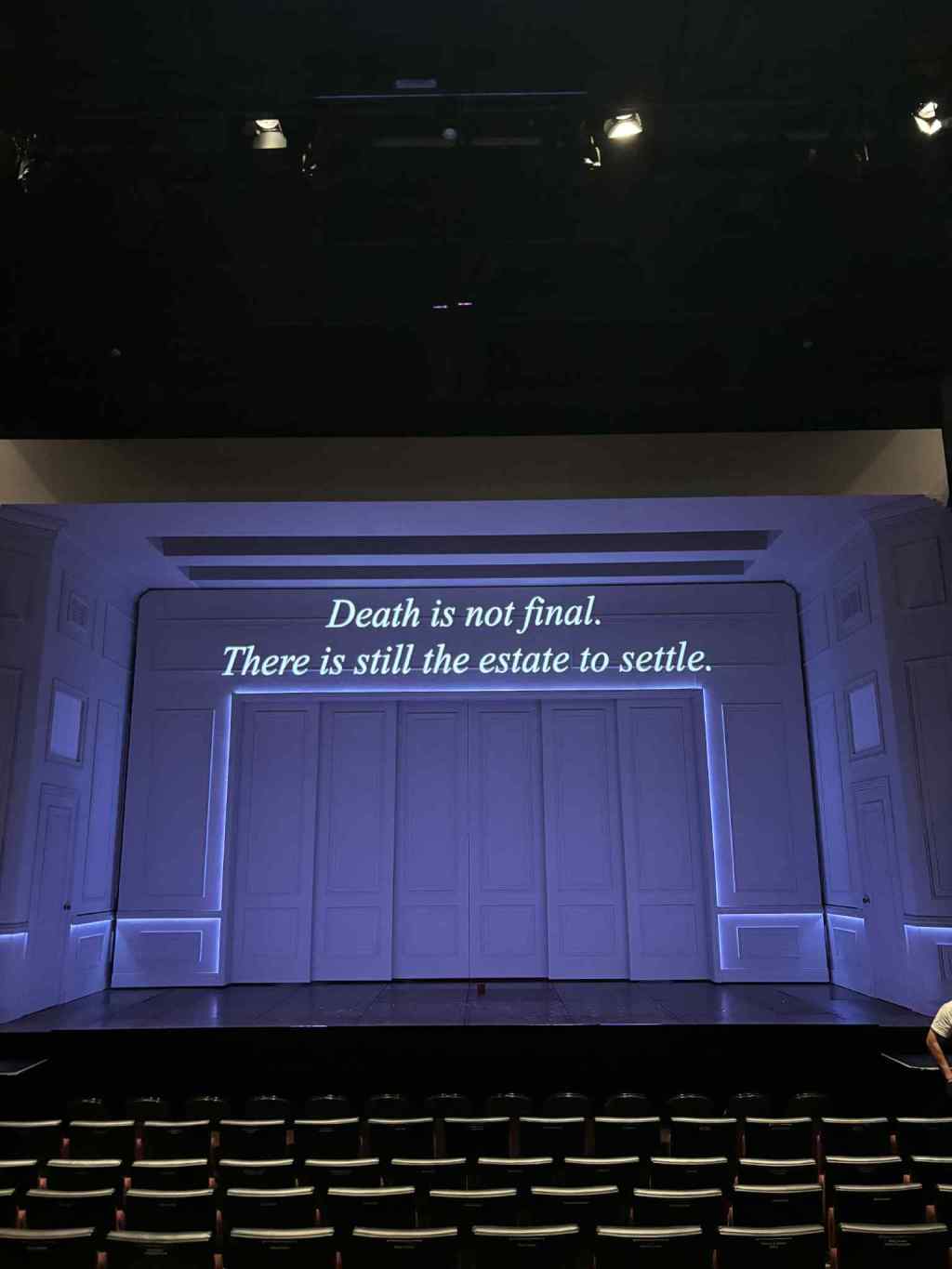

With impeccable (some may say almost surgical2) precision, The writer (Shaan Sahota) has delivered every bit of what one may expect from a good political play in the first twenty minutes of The Estate. The opening was packed with information without being overly expositionary: the (real and wannabe) politicians’ tongue-in-cheek way of tiptoeing around a sex scandal immediately gripped the audience because it was oh-so-painfully accurate. And the words uttered were marvellously complemented by those that were not. The (rather unfortunate) fact that over 50% of communication is nonverbal is perfectly captured in the characters’ interactions with one another. The power play between Angad (Adeel Akhtar), the protagonist and contestant for party leadership, and Ralph (Humphrey Ker), the party whip, was delivered in hmphs, pauses, tiny interruptions, and glances at smartphones. The slights were subtle, yet effectively delivered everyone who has been on the receiving end a painful sting. This, sprinkled with some wit reminiscent of the BBC classic Yes, Prime Minister when the cynical career politicians snubbed the naive idealism of Isaac (Fode Simbo), the access scheme intern, made the first half an absolute delight.

Even more painfully accurate was Sahota’s satirisation of Oxonians. In the programme, every Oxonian character had their college affiliation exposed —— a charming detail which I found very amusing —— and the characterisations were both specific to their respective colleges and scarily accurate. Ralph was essentially a generation of older Mertonians wrapped in a trenchcoat, and whilst the text itself never stated which exact college Sangeeta (Dinita Gohil), Angad’s wife, attended, her mannerisms somehow oozed Jesus College. And it was not just their college affiliations: Sahota even managed to convey which boarding school her characters had attended before university. Petra (Helena Wilson), for instance, was a spot-on archetype of an professionally-ambitious girl from an academically-focused all-girls boarding school, providing a lovely contrast with the rather more genteel and domestic Sangeeta. I felt like I had heard so many of those conversations somewhere in Oxford, and I have been selling this play to my friends as a ‘wonderfully (woefully?) accurate ethnographic (zoological?) study of Oxonians in their natural habitat’. All of these convinced me that the writer must have been an incredibly observant Oxonian who lived and breathed that bizarre bubble.

But this was way more than just a good political play. In parallel with the politics, the play developed a wonderfully-poignant storyline focusing on Angad’s rather awful father and the messy family drama he had left behind. Outside of the office and the leadership contest, Angad was a son with unresolved father issues and a little brother spoiled by his sexist and authoritarian father and two long-suffering sisters —- Gyan (Thusitha Jayasundera), a mother-like oldest sister who repressed her inner longings to mother her siblings, and Malicka (Shelley Conn), a rebellious second sister who flees the family, ironically via marriage. Sahota carefully dissected and psychoanalysed this canonical and almost cliché family configuration to give a painfully accurate depiction of the conflicts, dynamics and traumas rather common amongst South Asian immigrant families3. This made the entire world of politics seem rather small (which, one might say, is rather apt given the current state of politics). Moreover, Sahota’s portrayal of family was anything but soppy. Angad told his constituency that his father came from nothing, ran a humble local business, and offered new immigrants mango and chai —- but in reality he was an emotionally- and physically abusive man who had a portfolio of slum-like, legally-questionable properties which he rented out to new immigrants so he could send his son to Harrow. Likewise, Angad and his sisters talked about familial affections and swore that ‘it is not about money’ but it was oh-so clear that everything was measured in sums, whilst Sangeeta maintained her splendid isolation behind her father’s money. Having seen too many ‘hearth and home’ eulogy, the depiction of middle-class immigrant families in The Estate was wonderfully refreshing. And precisely because Sahota did not shy away from the ugly realities of family and culture, the rare moments of affection came across as particularly realistic.

I spent the entire interval anxiously devouring a tiny tub of vanilla ice cream, fearing a ‘drop’ in Act 2 because I was not sure how those various strands could be effectively woven together. Act 2, however, not only laid my worries to rest but also went way above and beyond my expectation. Plot-wise, it was rather foreseeable that Angad’s private troubles would bleed into his public life, yet what happened after the blow-up absolutely took me by surprise. Without spoiling too much, what seemed and felt like a political death sentence was overturned by Angad’s cynical-yet-ingenious ad lib on ‘our tradition’ and ‘multiculturalism’ at the party conference. Meanwhile, on the family front, instead of resolution, there is the beginning of another cycle. Everything was turned upside down yet nothing had changed. Power changed hands, but the new leader came from the same exact crop as the old, and politics was still hollow, hollow, hollow. Likewise, generational trauma survived the implosion of a family, and no one really came to terms with culture or migrant identity because, frankly, no one cared. The story thus got a perfect ending but no character received closure, leaving the audience simultaneously satisfied and wanting more.

I drafted this review on a euphoric adrenaline rush on my way back. It was truly one of the best productions I had seen in a long time, and I struggled to find a single weak link. The directing and acting brought out the best of the writing, and the stage, sound, and light designs were all phenomenal. Moreover, Sahota absolutely deserved every bit of her National Theatre debut, and I truly believe that we are witnessing a rising star that, given time, could well become one of the best British playwrights of this generation.

- The Estate is a new play by Shaan Sahota, at the Dorfman Theatre of the National Theatre until 23 August 2025. ↩︎

- The word is carefully chosen given that the playwright is also a junior doctor, and it was interesting to see elements of her experience working in healthcare throughout the play. ↩︎

- Though I can really only speak for East Asian ones. ↩︎

Leave a comment