3-3.5/5

I must confess that Lily Zhang’s Final Salomé1 has had the misfortune of my intimate involvement – observation or interference, depending on the perspective – in its creative process. The reader should hence understand that while my review is enriched with my knowledge of the play and its context, it will also necessarily be somewhat speculative about what an ordinary audience may experience.

The Play [Spoiler Alert]

The Final Salomé is an impressively well-researched and fresh, modern account of the life of Robbie Ross, Oscar Wilde’s forgotten literary executor and first male lover. It distances itself from the previous accounts, where Robbie is depicted mostly in his professional capacities and/or as a “devoted friend” of Oscar Wilde’s, conveniently keeping his homosexuality under wraps. Instead, the Final Salomé presents a refreshing image of Robbie not just as the friend and literary executor, not just as protector of poets and literary critic, but as Oscar Wilde’s lover and cross-bearer.

Structurally, Act 1 starts with the big themes: the political persecution and social marginalisation of homosexuals in Victorian England, exacerbated by the turmoil of the Great War. After the introduction of More Adey (Nikolas Nargi), our unreliable narrator, the audience is precipitated into the ridiculous and hilarious trial opposing protofascist MP Noel Pemberton-Billing (Charlie Lewis) and artist Maud Allan (Saffy Hills), whom the former accuses of turning politicians’ wives lesbian in service of the Kaiser with her performance of Salomé. The story then unfolds around whether Robbie Ross (Peregrine Neger), Oscar Wilde’s literary executor and expert of his work, should testify in defence of Salomé. Yet as the story progresses and as we learn more about Robbie through his flashbacks and his repeated rejection of speaking out in defence of Salomé, one gradually sees that the heart of the play is not, in fact, politics. The elephant in the room is carefully concealed by the shadow of politics, just like Robbie was concealed by the epithet ‘loyal friend’ in his own biographies.

Act 2 then dissects Robbie’s silence to reveal the complexities of his character. It replays the events of Act 1 from Robbie’s perspective, showing his struggles, complexities, contradictions, and his deepest convictions —— why did he ardently defend Wilde’s work, doing everything to protect Wilde’s legacies, going as far as producing whole new translations of Salomé; why did he ultimately refused to testify to protect Wilde’s legacy, and, by doing so, tragically devastating that very legacy; and why did he direct his ashes to be buried with Wilde in Père Lachaise? ‘Love only should one consider’ was the answer.

I have, since the beginning of the creative process, been terrified by how well researched Lily Zhang’s Final Salomé was. This is shown by how many lines are direct quotes from primary sources. Notwithstanding, the play employs an incredibly well-thought-out structure that seamlessly incorporates the necessary information without falling into the common trap of didacticism. I appreciated its abstractness: Zhang ingeniously reordered elements of Robbie’s biography to abstract away from the concrete historical timeline while concretising the abstract ideas of Zhang’s interpretation of who Robbie was.

Robbie is certainly not an easy person to depict. He is so complex and contradictory: he was self-erasing but egocentric in his own way, brave but weak in his own way, a fighter for queer liberation psychologically imprisoned by internalised homophobia. I particularly appreciated that Zhang made sure he was not erased more than he might have wanted himself to be. Oscar Wilde was not depicted —— a conscious and correct choice. The play also did not claim a full or accurate depiction of his complex character but only showed the blurry memories of More Adey in an asylum, a classic unreliable narrator. The natural mise en abîme between the narrator and narrated is reminiscent of Tim Price’s Nye. Additionally, Zhang employed a constant and very rich stream of symbolisms (like the green carnations) to distinguish imagined characters from their real life counterparts, which not only blurred the line between imagination and reality but also gave an almost psychoanalytic view of the characters (especially Robbie).

Under Zhang’s plume, the idea of Robbie is divided into a symmetric pair of abstractions: young and old Robbie. This is quite a brilliant idea: young Robbie (Ren Antoine) was lively, loving, sexual and, above all, has a sense of self; whereas old Robbie was jaded, repressed (and oppressed), and aggressively self-erasing. The production showcased Robbie’s self-erasure, but through his devotion to Oscar Wilde throughout Act 2, one also saw his talent and latent ego when they are channeled into his love for Wilde and poured into Wilde’s work. This contradiction underpinned Robbie’s complex character.

The play follows the psychological journey of the two Robbies. We see Robbie tormented by the oppressive society through the numerous flashbacks to his childhood traumas and the persecution he endured in and out of court, but also, more importantly, by the memories of Oscar Wilde. For instance, in one scene, in a rather biblical fashion, old Robbie kills young Robbie, who then resurrects, seduces him with an apple like he thinks he seduced Oscar Wilde, falls into the trap of love with the Majestic Beacon, only to be killed again by old Robbie in despair. The biblical imagery is present throughout the play, not only hinting at Robbie’s Catholicism but also pointing out his sacrificial spirit: always he acted as if in repentance of the ‘original sin’ —- that of ‘corrupting’ Oscar Wilde by introducing him to homosexuality. The biblical elements add a lot of weight to the tragic and cathartic final scene, where Robbie directs his body to be cremated, guaranteeing his place in hell. This made the said scene an absolute masterpiece, and it is difficult to articulate its ardent romanticism with words. I remember crying every time I read or saw it.

The other characters are no less colourful. Apart from the complex Robbie Ross, one remembers Lord Alfred ‘Bosie’ Douglas (Sebastian Cynn), whom I’ll shortly return to; Maud Allan, the embodiment of the play’s political elements and the artist behind Salomé —- an ardent defender of her art martyred by her defiance of authority and oppression; More Adey, unreliable narrator but also Robbie’s long term partner, who was always there for Robbie even when he was baffled by him; Olive (Annabelle Higgins), Bosie’s lesbian wife who ‘tried to cure him’, whose subsidiary position to Bosie is analogous of Adey’s…… There is a true plethora of queer characters, each oppressed, repressed, and complex in their own ways, each given a worthy part in the historical fabric that the play tries to weave, and all intertwined by the symmetries that Zhang tries to build through techniques such as deliberate multi-roling.

In particular, we see Bosie, the other more famous ex-lover of Wilde’s, as the dark mirror of Robbie Ross. Both were tormented by internalised homophobia, traumatic experiences related to Wilde, and (albeit in different ways) egocentrism; yet whilst Robbie directed his hatred inwards, Bosie projected outward towards the ghost of Oscar Wilde. This was perhaps understandable given how pivotal a role he played (and was seen to play) in Wilde’s downfall. Therefore, after the Wilde trial, Bosie tried to rescue his reputation and cleanse himself of shame by marrying Olive, having a child, and relentlessly suing anyone who brought up his association with Wilde (including Robbie), in order to convince himself and everyone else that he had ‘cured’ himself of homosexuality. Despite this, in the play, Bosie is not depicted as a simple ‘villain’: rather than pitting him against Robbie, Zhang decided to highlight the symmetry. Thus, we see Robbie and Bosie continuously haunting each other throughout the play, with neither really understanding the other. The quid pro quo was most obvious in an elegantly structured scene where Robbie confronted Bosie who just gave a devastating testimony against Salomé that backfired spectacularly and resulted in his own public shaming, which made clear that the two are, in fact, different sides of the very same coin as victims of systematic persecution and marginalisation (and, arguably, also of Oscar Wilde’s lust).

The Production

When reading Lily Zhang’s final draft, I was struck by the elegance of its structure and the beautiful writing of certain scenes. This is perhaps why I was underwhelmed the first time I saw the production, surprised by all the imperfections I had not picked up in the script. This is not to say that the production was not good: as I shall detail in the second part of this review, it was actually remarkable —– the cast and the crew pulled off what could be said to be one of the most impressive student productions I’ve seen in my four Oxbridge years in a small lecture theatre with a wide but shallow stage. Therefore, I was laughing and crying every moment during my second watch, but during the first night, I couldn’t help but be distracted by its flaws.

The structure of the play largely worked well. The progression from Act 1 to Act 2 was good, and I did appreciate how Act 2 replayed Act 1 by contextualising and clarifying some of its confusing elements. The double plays, parallelisms, and mises en abîme were on point. I especially appreciated the moments where the different symmetries were made explicit, like when Bosie brought his imaginary young Robbie to court. Additionally, the asylum was well used at the beginning and the end of both acts to give an overall narrative structure to the play. However, admittedly, a trade-off had to be made: the asylum grounded the structure of the play by giving it an essay-like introduction and conclusion, but at the same time, it removed the potential for alternative dramatic effects obtainable by ending the two acts at more important points of the story.

The staging was honestly impressively done. In a lecture theatre that had barely any stage depth and several unmoveable objects (including a podium and a grand piano), the crew really made it work using relatively simple props and minimal modification of the stage itself. Here are a few elements. The width of the stage was well exploited, compensating for its lack of depth, through different configurations of four wooden boxes: when stacked together, they become the lawyers’ podiums in the courtroom, and when unstacked, they are bookshelves in Robbie’s home. To further compensate for the lack of space, the crew also uses the entire available space in the lecture theatre; the audience sees Bosie and the ensemble walking down the aisles, Robbie running around the theatre, exiting from one door and entering from another. The lighting also helped build up the atmosphere at multiple occasions: the dim lights used for scenes in Robbie’s memories, the eerie cold lights in the mental asylum, the strong lights focused on Robbie who was questioned about his sexuality, the surreal purple lights when Allan presented her vision of Salomé were all very adequate. The small items and the costumes were simple but exquisite: they had the flavour of Victorian England but were not excessive in the manners of Victorian theatre. Moreover, they carried significant symbolic weight (e.g.: the green carnations). I did also appreciate the ample references to both Strauss’ and Wilde’s Salomé in the script, the set, and the sound, despite imperfect sound quality.

I was worried that acting might be a bottleneck to the quality of the production given the play’s complexity. I have to say that my fears were wholly laid to rest. I was blown away by Peregrine Neger’s performance, which, I have to say, really took the show to another level. He truly breathed life into old Robbie in a way that corresponds well to the image I had formed of Robbie when reading the script and discussing it with Lily Zhang. His performance compellingly captured both the lightness of Robbie’s façade and the depth of his internal struggles —- it was definitely at the level of a seasoned professional actor. He also demonstrated his linguistic skills in the scene where he had to read several letters in completely different languages. But these paled in comparison with the penultimate scene, where Neger’s acting talent really blazed through with impressive effect. The rich emotions in his lines delivery, his trembling hands, his tears and his smile of relief when reading Robbie’s final letter was incredibly moving and truly unforgettable. I can only describe his performance using Horace’s words: si vis me flere, dolendum est primum ipsi tibi. That particular scene, and the show in general, was complemented by Ren Antoine’s solid performance as young Robbie. Most memorable was how expertly he handled the very erotic scene, where he forcefully feeds old Robbie an apple. Sebastian Cynn showed the expected amount of hysteria and self-importance when incarnating Bosie. The emotional explosions were quite impressive, and the transitions between different versions of Bosie (imagined/actual) were convincing. I also particularly liked his double-roling as the official receiver, which was absolutely hilarious. If I were to nitpick, I have to admit that I found Bosie a bit too loud sometimes —- therefore, some of his crucial lines, such as ‘Do you think I care for his affection’ in the confrontation scene with Robbie, were not well articulated. Saffy Hills’ Maud Allan had the opposite issue: she delivered a convincing and passionate performance of the artist but sometimes lacked projection. The clown characters —- Pemberton-Billing, Humphreys (Lily Zhang) and the judge (Annabelle Higgins) —- delivered exactly what they set out to deliver: a nonsensical protofascist, an almost-cartoonish caricature of an incompetent lawyer, and a conservative Victorian judge. I have to commend Zhang’s performance as Humphreys for showing her great potential for a legal career; the same could not be said for her Vyvyan Holland, whose interaction with Robbie was rather awkward and exposed her inability to be an affectionate son. There was very little to reproach on all the other characters.

This is not to say that I did not have any complaints.

In Act 1, my biggest issue is that it focused too much on how others saw Robbie, which made Robbie’s own character rather flat and the structure more repetitive than it should be. This was a surprising discovery I made while watching the play, for I had the opposite feeling when reading the script. Act 1 as it currently stands intersperses Robbie’s traumatic memories with three successive dialogues with Maud Allan, More Adey, and Vyvyan Holland & the Movement, where they try to get him to defend Salomé. While the structure repeats, the scenes were not meant to be repetitive but were rather intended to peel away layers of Robbie’s excuses. However, when watching the show, I found Act 1 rather unproductively repetitive. I conjecture two reasons for this feeling. Firstly, the layers were unclear, because the progression was considerably watered down by the length of the dialogues and the indirectness of Robbie’s lines. Secondly, and arguably more importantly, even if the layers were clearly conveyed and properly understood, they would not have been sufficient to make the audience feel like they were making any progress in understanding Robbie. I remember feeling quite frustrated because while a lot of information was provided during Act 1, they seemed disconnected, shallow, and, above all, unhelpful in bettering my understanding of Robbie. My impression was that immediately following every flashback, Robbie would give the shallowest possible reason for not testifying that can be logically deducted with minimal information about his experience: if he was persecuted in a previous flashback, he would immediately say that ‘they won’t listen’; if he was lynched by Bosie in court, it would be implied in the next scene that he is refusing because of fear for Bosie. It was not immediate that these were excuses and partial truths, that he was showing a façade, or that he had any complexity beyond the surface. I think this was a missed opportunity. Admittedly, the illusion of shallowness could have been intentional, or even historically accurate from his letters. Nevertheless, I maintain that the play might benefit from a stab at Robbie’s real fears (or at least some fragments of his deepest anxieties) in Act 1.

I must admit that Act 1 flowed much better than I expected (and much better compared to Act 2) thanks to the wit in its lines, the smoothness of its transitions, and the effective use of props and the space. One could argue, however, that sometimes the wit, when inserted amidst serious conversations, could be distracting —- although I did not find it too excessive. For instance, I did think that Bosie’s loud interventions could be made less frequent, less because of the wit and more because of the interruption. My biggest concern is, however, with the scene in Act 2 where Robbie fights everyone to defend Oscar Wilde’s estate. It is an important scene which shows Robbie’s convictions and his hard work, clearly inspired by BBC’s Yes Prime Minister. I would argue however that it is excessively long and unnecessarily repetitive. Moreover, in the show, sometimes comprehensibility was compromised for dramatic effect: the intervention by André Gide with the artificial and incomprehensible French2 accent stood out as an example. Perhaps the first time where Robbie snaps and screams ‘now what’ was a good moment to cut the cycle short and show some actual progress.

Like some parts of Act 1, Act 2 also suffered from dialogues that lacked the depth that the situation warranted. When Robbie saw Bosie testifying in the Allan v Pemberton-Billing case, for instance, his reactions were somewhat lacking in depth and gravity: he seemed lightly disappointed by his miscalculation, and much of the disappointment was directed outwards towards Bosie; however, I think Robbie would have been more disappointed at himself than disillusioned with Bosie, and would have engaged in some sort of self-flagellation over his own absurdity (and naïveté) in trying to make a nonexistent pact with an imaginary Bosie. This was more of a writing problem than an acting problem, for the lines hinted at the former when they really should be aiming for the latter. The subsequent confrontation was also a missed opportunity for adding more layers to the Bosie-Robbie duo: Robbie came out of it fully triumphant, but to me, it should not have such a cathartic resolution because the confrontation should have been a rather tragic instance where two deeply-hurt and similarly-tragic men stab each other emotionally where it hurt the most in a winnerless duel. Moreover, because they mirror one another, every stab at the other should also cause an equal part of bleeding in oneself, so this scene should not only showcase how pathetic Bosie was, but also Robbie’s insecurities, weaknesses, and imperfections.

Finally, there were also facts, contexts or abstractions which should be made more explicit. For instance, it was unclear to me whether the green carnation was sufficient for the audience to understand the distinction between imagined and real characters. This might be unfair: after all, I am speculating on the experience of the average reasonable member of the audience, of which I certainly am not one. What I did find unclear, however, is the fact that Robbie was imagining himself making a deal with Bosie right before the scene of Bosie’s testimony, for it was not very explicitly presented as so.

I do want to stress that these criticisms are quite nitpicky and by no means undermine the integral prowess of the writing and the production of the Final Salomé. It is difficult not to be impressed by such a well-rounded student production, and even more so when one learns that this is Lily Zhang’s first ever play.

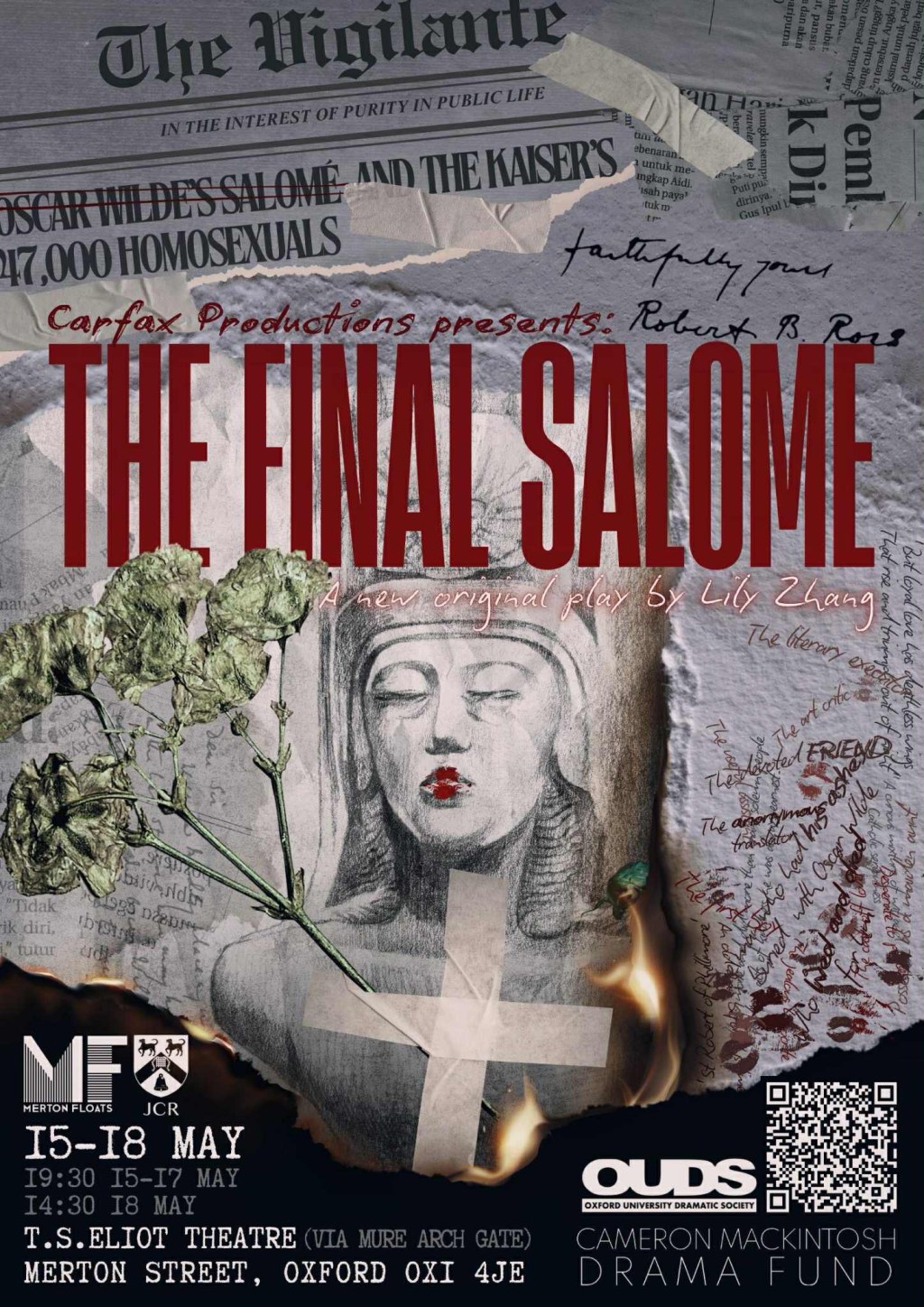

- The Final Salomé is Lily Zhang’s original new play, produced for the first time at the T. S. Eliot theatre of Merton College, Oxford, between 15 and 18 May 2025. ↩︎

- I am French and it was not what a real French accent would sound like. Rather, it sounded like a language enthusiast’s phonological exercise. ↩︎